By Sargon deJesus, Science Writer and Analyst,Anthony Amato, Senior Climate and Energy Analyst, and Robyn Liska, Climate and Energy Analyst, Eastern Research Group

(This article appears in the October, 2010 issue of The ACUPCC Implementer)

When signatories take the first step of self-discovery by starting to craft a Climate Action Plan (CAP), many discover that the journey is more of a grueling uphill climb. Every school faces challenges that set back their climate action planning – entrenched operations, cost, lack of community buy-in, constraints on staff time. What can your school do to avoid these obstacles? To help answer this, a new report byEastern Research Group, Inc. (ERG) details important best practices in creating a CAP by analyzing completed reports and speaking with schools directly. Through the support of EPA, the recently released study “Climate Action Planning: A Review of Best Practices, Key Elements, and Common Climate Strategies ” identifies helpful approaches that any signatory can start using for their first CAP or future update.

What is the best way to structure my CAP development process? Who should be involved in making decisions? How do I present or share information with key people? What do I include in the CAP? What metrics do I use to track my school’s progress? The report surveyed 50 completed CAPs and conducted two dozen interviews with school representatives about their unique experiences to answer critical questions such as those.

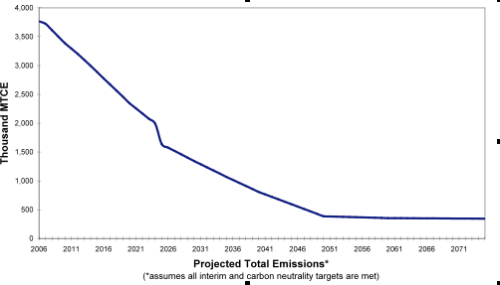

ERG’s survey included an array of 50 colleges of all sizes, regions, and breadth of degree offerings. The results from this research shows ambitious trends across the schools. When combined, these climate commitments represent a significant reduction in carbon emissions and exemplify the power of the ACUPCC. The figure below illustrates the reductions in the total emissions of these 50 schools over time, assuming they achieve all of their interim reduction targets and neutrality goals.

Much work lies between now and the low-carbon future depicted above. Before even thinking about implementation, schools have to compile data, organize support, and decide on how to present information about their institution. To make this part of the CAP process successful, schools need a management structure that truly works. Some schools choose to create a central committee with stakeholders from groups inside and outside the campus walls. This collaborative approach builds strong ties and motivation among key players, but demands a heavy time commitment and lengthy deliberation. Other schools opt to put the work in the hands of a central point person. Relying on a small team of core advisors, this climate “superhero” develops the plan before presenting it to a higher-level body for approval.

No matter how you structure the decision-making process, school officials say the most important element is to have good communication. It starts with clearly explaining the purpose of the climate commitment and how a CAP fits into that. School representatives categorically believe in the importance of introducing these concepts to all members of the community early on to build buy-in for the climate commitment. In one example, to create motivation and to encourage communication about Arizona State University’s climate commitment, the university established a working group of senior-level administrators. These officials regularly meet with the President to report on CAP implementation in their departments. By forging communication channels early on in the development of the CAP, these pathways can help make implementation easier down the line. Many representatives also point out that effective communication allows for people who think differently from administrators or facilities managers to have their say. For example, the University of California, San Francisco devoted part of their sustainability website to solicit suggestions and comments from the campus community.

Creating a GHG inventory is a key ingredient of a CAP and demands considerable effort. To ease this burden, some schools choose to hire consultants to help carry it out. These schools, which often lack the expertise and technical familiarity to conduct a GHG inventory, find consultants to be a useful and important contributor to the process. Their experience can often help accelerate the construction of the inventory or other aspects of CAP development, such as financial evaluation of potential mitigation options. On the other hand, schools that opt to keep things in house often find their inventory experience to be more rewarding. Paul Manstrom, Director of Facilities Management at Kalamazoo College, explains that “it allowed a cross-section of people to gain expertise on the issue and [now there is] a permanent presence on campus of people who were able to speak to the issue.” With or without outside help, however, school representatives felt that the decision they made was the right one for them at the time.

Once schools make the move from brainstorming and data collection to concrete planning, school representatives consistently recommend integrating the planning with ongoing campus activity. Has your campus already started a sustainability initiative separate from the ACUPCC? Does your school face a largely under-informed community or skeptical staff? Choosing what strategies to use in your CAP is as critical to getting community support as having good communication channels. If a CAP appears to challenge existing projects or to deprive other departments of their funding, it can be viewed with hostility. Preventing this kind of backlash first requires setting yourselves up for success.

In one example, the University of Arkansas is utilizing a two-phased approach to help promote sustainability over the long term. To help build campus support, officials are prioritizing highly visible and “photogenic” projects, despite their sometimes smaller impact on GHG emissions. These projects include biking infrastructure, biodiesel, and recycling. Once sustainability anchors itself in the community, administrators will shift their focus to bigger items, such as emissions from electricity generation – something that could not happen without firmly rooted campus support. While this approach is not appropriate for every school, it shows the need for schools to tailor their approaches to their unique situation.

The statistics from the survey of CAPs echo what many of the representatives expressed verbally during the interviews. The graph below shows an example from the report of how schools are mobilizing various mitigation strategies. Frequently mentioned strategies, such as energy efficiency and transportation measures to decrease Scope 3 emissions, are well represented across all schools. Other data presented in the report offer context for schools unsure about how to prioritize their strategies. Through this wide survey of CAPs, the data provide a good portrayal of how schools structured their plans and addressed the core areas of the American College & University Presidents’ Climate Commitment (mitigation, education, research, and outreach).

Formulating a CAP and creating an integrated plan entails meticulous planning, along with frequent wrong turns and unexpected successes. No matter if you are just starting your CAP adventure or confidently starting your next CAP update – by taking note of these lessons from other schools, your institution can avoid similar trials by fire and can finish with a more refined, and ultimately more successful, product!